How Sam Nowell made the leap from studying architecture to launching a sustainable fashion line

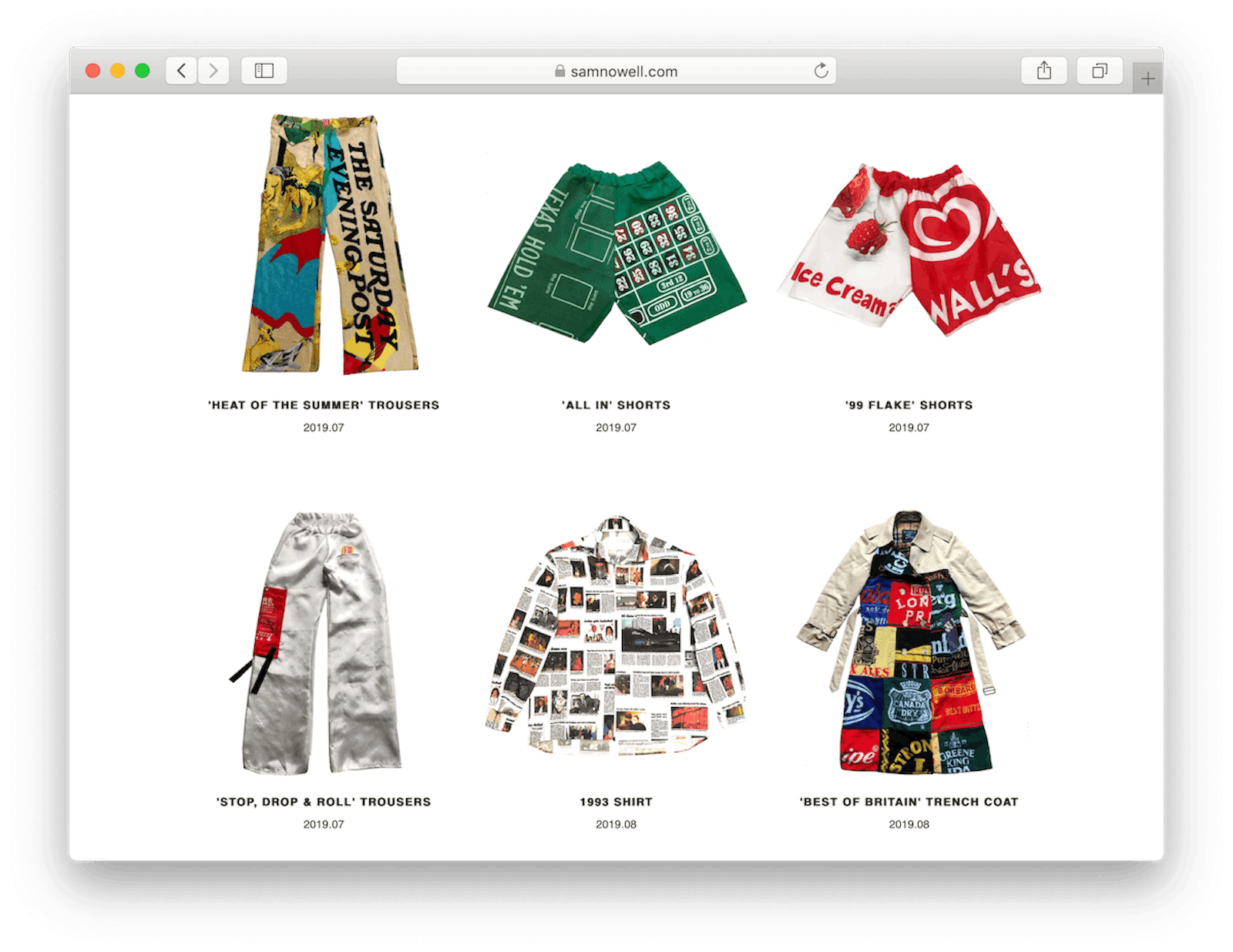

Sometimes you end up on a path that could never have been predicted by your degree subject. This was the case for Sam Nowell, a Manchester-born, London-based fashion designer and creative. Studying architecture at the University of Liverpool, it was during his first year that he thought he’d try out a little bit of sewing and fashion design. Little did he know that his side project – on-point garms made from salvaged fabrics – would become a huge hit, and that he’d end up collaborating with the likes of Wimbledon, Selfridges, TATE, Depop and The Basement. Having graduated last summer, we caught up with Sam to find out how he made the switch from architecture to fashion and got his tips on launching a label.

From buildings to clothes

I started drawing clothes while in my first year of university studying architecture. You’re given a sketchbook and I found myself drawing clothes more than buildings. I always thought that I wasn’t just at an architecture school learning how to build buildings.

I wanted to be involved in the creative process and have an outlet where I could run out this energy – it was important that I had something for my hands to do. I started by printing t-shirts in my university bedroom, but I became bored of it pretty quickly. It’s a good starting point, but I always wanted to learn and create more.

I had drawn up designs for dresses and jackets that I knew I wanted to make, yet the only thing stopping me was my ability. I eventually bought a sewing machine, then I just started experimenting and messing around on it.

“I think the sustainability side of it, for me, is almost a by-product of what I make.”

I think using old fabrics is really important and will be for a very long time – it’s also very on-trend to be sustainable. There are a lot of brands and individuals simply jumping on it for that reason, and in some cases to keep stakeholders or customers happy without really taking too much care in their output and process. I think the sustainability side of it, for me, is almost a by-product of what I make; I only use second-hand fabrics and materials because it’s cheap and available to me. However, I’m really keen on keeping things sustainable as I grow as a designer.

How architecture influences his practice

I think my architecture education has fed my clothing career. For three years I was lucky to be in a creative environment with like-minded people every day, and I got a lot of ideas from what happened in those design studios – whether it’s walking past a desk and seeing a drawing, picking up an architecture book or watching someone present a model. People don’t usually link clothes and architecture, but they’re very much intertwined as disciplines. The creative process is very similar, it's just that clothes are a lot ‘easier’ to create than buildings. I place the word ‘easier’ in inverted commas with a little caution there.

Learning how to sew

Being self-taught is a strange thing because it’s never necessarily true. I was very fortunate in my first year to have a good friend called Rowan lend me her sewing machine for days on end. She helped me find my way around it, started teaching me about sewing and gave me ideas to build upon. I’ve never really thanked her for it but she was really instrumental in getting me here, if here is anywhere at all.

I then built up my skills through YouTube videos, alongside trial and improvement. I put my sewing machine through hell and went through a lot of needles, but constant practice and finding things out for yourself is really important.

I work from my bedroom in North London. I use a Janome machine, and for my fabric and materials I will look in charity shops, fabric shops, vintage shops, job lots or eBay auctions and grab whatever I can.

“I put my sewing machine through hell, but constant practice and finding things out for yourself is really important.”

The toughest parts so far

I think there are two big challenges when working on projects like these. The first is keeping a constant output; it’s tricky to rely on charity shops or car boot sales for your materials. This is because occasionally you can go two weeks without finding anything, and other times always have things ready to be made. It’s hard to keep it constant and keep busy. The second challenge is working with very unpractical materials. Often I’ll throw fabric under my sewing machine needle and just hope that it sews. There’s a lot of trial and improvement involved with things not always working out.

I’m really thankful for the opportunities that I’ve had and the people that I’ve been able to meet so far. People really seem to connect with what I’m doing and I’m humbled by some of the responses I get. Things that stand out for me are stuff like the Wimbledon collection and the Tate gallery throwing my work on its walls. I really believe that (most) of the things I create are ‘art’ and to have the Tate recognise that was really special.

Goals for the future

I’d really love to be a part of the industry. I’m not sure if the projects I’m working on right now are for life, as I almost see them as some kind of loose stepping stone into being where I want to be with all of this. One of the greatest things I’ve learnt is to take care of what you create, focusing on the details and giving each item an individual aesthetic and unique characteristics.

In the future, I’d also love to be able to have this as my main source of work – until it takes me further at least. As I mentioned, these projects are only really intended as a documentation of my experimentation and to aid my skills and knowledge. I’d love to do large-scale projects with some brands that I look up to. There are some that I hope will be more than an email thread this year, but we will see.

...

Header image taken by Danny De La Bastide.

Introduction by Ayla Angelos

Mention Sam Nowell